Sunday, Day 92

A dead tree at the Aburi Botanical Garden in the process of being carved in the traditional Ghanaian manner by a local artisan.

Tema, the main port of Ghana, is located 19 miles south of the capital city of Accra. As one of our guides reminds us, it is in nearly the middle of the world, lying very close to both the prime meridian (0 degrees longitude—otherwise known as the GMT or Greenwich Mean Time) and the equator (0 degrees latitude).

Just like the ports of India, we can smell Tema a long time before we dock. Later we find out that that is because, in part, and just as in India, much of the rest of the developed world ships its electronic and other waste to Ghana for recycling. Europeans who think they are doing a good deed, individually, to pay 50 Euros to have a computer or other electronic device recycled responsibly are actually paying 49 Euros to profiteers to ship those items for 1 Euro to Ghana where some of the components are recycled but far more is burnt—at tremendous cost to both the environment and the health of workers, some as young as five years old—to recover metals as cheaply as possible. One of our professors takes an environmental risk class to visit one of these waste fields where over 60,000 families live in slums with no schools, no clinics, no power, no piped water or sanitation of any kind. Just open ditches and a road coming in and going back out. Despite the deplorable conditions, the community’s leaders are concerned that the class’s visit and associated publicity may harm the pipeline of waste without which its people have no livelihood.

And people even in this “wasteland” are still amazingly kind to us as visitors. When a student slips and falls into one of the many black pools of sludge in the narrow lanes of the squalid slum, all of us laugh—faculty, students and slum dwellers. The student is not happy, obviously, but what really shocks him is how quickly people haul small buckets of water from their shacks and bring rags to help clean the filth off him. It is a moment in one of the many lessons we learn about how hospitable people in grinding poverty still try to be.

Recently named the “Second Least Failed State” in Africa, after Mauritius, the country of Ghana is basically a success, no matter how much of a Third World country it looks to visitors. And that may mostly be a testament to an exceptional, charismatic, far-seeing leader who fought for independence from the British in 1957 in a largely peaceful campaign and yet who is now pretty much forgotten outside of Africa—Kwame Nkrumah. Born in the Gold Coast area that would later become Ghana and educated in Britain and the US in the 1930s, he is remembered as the first African to lead his nation to statehood. Today he is revered alongside Nelson Mandela as sub-Sahara Africa’s greatest leaders. In addition to articulating a compelling vision for Ghana that pulled together the many tribes in the country—in stark contrast to what is happening in so many African countries with ethnic violence—Nkrumah also sought to advance the cause of peaceful cooperation in pan-African unity. But a military coup in his own country removed him from power in the 1960s, apartheid forestalled a more gradual integration of blacks and mixed races in South Africa and Zimbabwe (previously Rhodesia), and the political elite in Ghana accelerated a course of rewarding itself that has now become a system of endemic corruption not unlike that of India.

In my reading I learn that the presence of malarial mosquitoes in the several countries of the Gold and Ivory coastline in West Africa helped prevent white settlers from coming in and claiming large tracts of land. The heat and malaria both meant that resources and labor were contracted through local tribal leaders. That made the drive for independence and its aftermath much less difficult because—in contrast to South Africa and Zimbabwe—there were not large numbers of prosperous white farmers or miners in residence. Basically, the British colonial administrators were relieved to leave the country.

Sorry for the history lesson but I learn a good deal about West Africa because I am asked to work with both the inter port lecturer and inter port students from Ghana who join us in South Africa for the days of class at sea coming to West Africa. The inter port lecturer is a well-educated and respected member of Ghana’s African University faculty and it quickly becomes apparent that the two students consider it disrespectful to disagree with any of the older gentleman’s views. They stick to non-controversial facts about the country and he speaks about proverbs, widespread tribal and ethnic harmony, progressive social programs and the need for Ghanaians to mostly work on restoring their cultural heritage and self confidence. I don’t get anywhere in trying to get them to address the tough issues of tribal/ethnic strife, child labor, and inadequate public infrastructure.

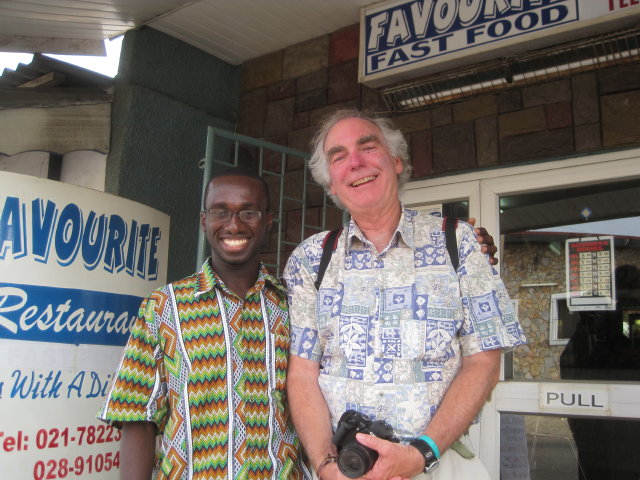

Later we hear a different story and get a much more complete picture when we speak to a young Ghanaian, ‘Michael’ Fifi Quansah, a former student who has worked with Warner while studying at the University of Virginia (both pictured above in front of Favourite Fast Foods). He fills us in on the considerable ethnic conflict and widespread corruption. He and other young people, educated in both Ghana and abroad, would like to be active and involved in a more progressive government but their participation is discouraged by the older political elite. The latter want the younger generation to serve their dues for many more years. Meanwhile, a wide gulf of inequality in the society persists as the elite and civil servants reward themselves and corruption becomes institutionalized—again much like India.

Having said all of this, the economic situation in Ghana is gradually improving and has reportedly come a long way in the last 10 years. But it seems to have a long way to go in our eyes. Again, like India but not quite so badly, the infrastructure is a patchwork and roads are clogged with vehicles in bogged-down traffic. Expensive gated communities are surrounded by shacks in slums which, in turn, are ringed-round with even more gated communities and busy dirt roads and highways. On-site, handmade concrete blocks are the building material of choice, so the McMansions here take a long time to complete. We learn that interest rates are exorbitant—25% or more—so most do not borrow but build very incrementally.

A surprising fact we learn about Ghana—as well as much of Africa—is the astounding growth of Christian churches on the continent, especially in the sub-Sahara, with one professor predicting that the next heads of both Catholicism and Anglicanism could well be from either Africa or South America. Many of us on the ship have spirited discussions about what this means for the future of these countries, still deeply entrenched in poverty and corruption that forestalls a much wider sharing of the very real and rich resources they contain. Billions of dollars of wealth have been extracted for many decades but are clearly not being used to benefit the society at large. Could African Christianity really make the difference in a peaceful transfer of more resources to the poor while they are alive, or will it go the way of colonial Christian models that put off any social justice to the afterlife?

To go the 19 miles from Tema to Accra is a big deal, at least an hour each way and far more in a jam, so going out to travel the country is not a decision made lightly. On the first day in port, Warner, Nancy and I hop the very first shuttle out and are deposited in Osu, a part of Accra where governmental offices and shops are located. It’s a rude first landing because we can’t match up our map with the streets or landmarks and for a good while dozens of us pass each other going in circles. We have a lunch meeting at the Favourite Foods Restaurant with Warner’s student, who now lives back home in Accra, but we can find no one who can tell us how to get to it. After much walking and a couple of taxi drives in misguided goose chases through the city, we finally find a policeman who knows where it is. That turns out to be within two blocks of where we started when the shuttle dropped us off next to a garish purple and pink, high rise night club. (Taxi drivers in many of the cities we visit on this voyage often don’t know the town they’re driving in. They are often from another country. It can make it very hard to choose a good one or feel confident they’ll get there.)

In the midst of all the running around, I am glad to get the chance to make a quick visit to the tomb and memorial park of Kwame Nkrumah near Independence Square.