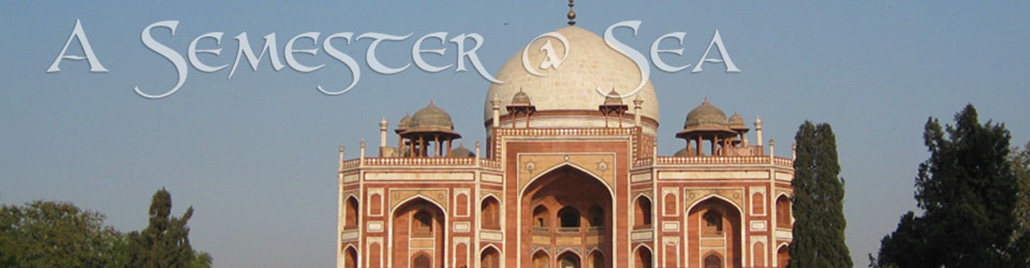

First, the good news on the major tourist sites in the north: Many are now UNESCO World Heritage Fund sites and there are substantial, ongoing efforts to stabilize and care for them, as well as to provide security services. They are as spectacular as ever and we see quite a few on our demanding itinerary: the truly breathtaking 17th century Taj Mahal that turns everyone who expects it to be just another overblown attraction into a believer in the power of love and exquisite beauty; the Mughal dynasty’s seat of power at Agra Fort across the river from the Taj; the now almost sinister compound of red sandstone palaces in the imperial 15th century deserted city of Fatehpur Sikri; Humayun’s Tomb, forerunner of the ornate Mughal style of architecture later perfected in the Taj Mahal; Qutub Minar, a 71-meter high fluted minaret from the 13th century; and the Hawa Mahal, Amber Fort and maharaji pink sandstone city gates and palaces in Jaipur. We also visit Old and New Delhi, the embassy row of Rajpath near the India Gate, Parliament House, the Red Fort of the Mughals, and the Gandhi Raj Ghat marble slab commemorating the site of his funeral pyre. The last site is set in a huge city park where families meet and play with their children. Inside the park is one of the few places our group is not completely beset by hawkers. Instead, we get a chance to speak with Indians and take photos of each other. As we leave, the sun is setting and it is a beautiful sight to watch people line-up and pay their respects at the Gandhi memorial.

School students we meet and speak with in the park.

School students we meet and speak with in the park.

All of these masterpieces of India’s past are difficult to reconcile with the India of today. It is hard not to wonder what happened to the painstaking craftsmanship and massive engineering projects involved in these monumental structures. India obviously has intelligent leaders, dedicated educators and hardworking engineers but it doesn’t seem to be able to put solutions together well enough to make a difference on the scale required by its size and population. There are too few roads, too many cars, too many people, and too little that actually works together in an effective whole. I take one photo of a massive traffic snarl within two blocks of the Parliament building and across from slums that is emblematic because none of the traffic signals work (no one pays attention to them when they do). Across from the stirring site in the park at Gandhi’s memorial is a coal power plant in full view belching black smoke; the next day, along the railway route to Agra, we see that a tall derrick or tower is dramatically on fire and no one even seems to notice. (On the other hand, as surreal as a 6am scene at the Delhi Central Railway Station feels, and as battered as the first class passenger compartments appear, the long-distance tracks we ride from Delhi to Agra are much smoother—and the train’s speed much faster—than anything except the Acela in the US. How many more years will it take before we go into irrevocable decline—because we don’t have leaders who can work together for a greater good—and we become India?) When second class passenger trains come up alongside our first class compartments, we see how jammed with people and alive with cooking, cleaning, eating and washing they are—almost as though an entire village had moved onto the train. It would take Dickens to adequately describe Indian railway stations and cars.

This photo is the best of a lot of photos that did not come out at all at the Delhi Railway Station at early dawn in the already crowded station. It is taken through the cloudy window of our rail compartment. It shows an old man very tenderly holding a young child for a woman, perhaps his daughter, while she tries to find a porter for their luggage.

This photo is the best of a lot of photos that did not come out at all at the Delhi Railway Station at early dawn in the already crowded station. It is taken through the cloudy window of our rail compartment. It shows an old man very tenderly holding a young child for a woman, perhaps his daughter, while she tries to find a porter for their luggage.

Humayun’s Tomb, forerunner to the Taj Mahal.

Humayun’s Tomb, forerunner to the Taj Mahal.

The aural counterpart to the ever present smoke and haze of pollution is the continuous noise of honking on the part of any and all vehicles—excepting horse-drawn and people-powered lorries and sedan chairs. I take it all back. Remember when I said that Vietnam’s traffic had to be the worst in the world? Well, it is a mere pup in the annals of nightmare traffic. India is the venerable heavyweight elder. No one drives a bus without a second person riding lookout. It’s not uncommon for vehicles on a four-lane highway to go the wrong way and without their lights on at night. In most cases there are no lane markings and no one pays attention to the notion of lanes anyway. There are no restrictions on who walks or runs or pushes a cart down a road. Everyone’s on the road together: Sacred cows lay down in the medians or along the curbs of most busy streets when they’re not wandering idly across; dogs genetically gifted with the trait for how to look both ways and cross impossibly packed roads; pigs and goats eating as much garbage as they possibly can before the remainder is set afire to burn.