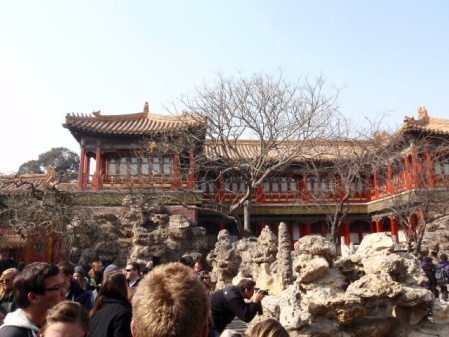

The only day we have beautiful blue skies anywhere in China—skies actually get even worse by the time we get to warmer Hong Kong—is the day we visit the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square and I manage to forget to return my charged battery to my camera. (The couple photos here are courtesy of student Andrew Peper, one of our library student assistants.)

Americans remember Tiananmen for the students’ protest that was brutally crushed and broadcast on American television. The Chinese remember it for the soldiers who were also killed when the students fire-bombed their tanks. Regardless, the event was a tragedy for both students and soldiers and Tiananmen is indisputably the world’s largest public plaza, accommodating 1 million at a time and it is truly an astounding and moving experience to be in it with nearly that many Chinese people visiting the central place of assembly in their country. It was in 1949 that Chairman Mao spoke from the northside rostrum to the Chinese people and proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

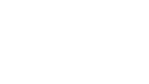

The Forbidden City and Imperial Palace is an immense complex of 8,760 rooms that were home to 24 emperors beginning in 1420. An estimated 8,000 to 10,000 people lived their entire lives behind its high, forbidding walls surrounded by a wide moat. The huge crowds make it difficult to keep track of everyone and we spend a lot of time re-grouping and re-counting. After struggling to get through four sets of gates and enclosed compounds the adults in our party all come to the conclusion that barcodes on people would be perfectly acceptable to keep track of tourists—never mind the Animal-Farm overtones. The final garden gate at the northern end encloses an intimate garden for the Emperor’s inner circle that shelters 300-year-old cypresses and water canals.

In the afternoon we go to visit the Guan’ai Migrant School far outside the city to the south in Shunyi for a service visit and volunteer work. After thinking about this visit for a long time, I am still not sure how I feel about it—particularly in terms of the contrast between our privilege and their poverty. I’ve read a book while in Japan—Learning to Bow—about an English teacher who also struggles about whether token visits of Americans are good or bad. He learns of cases that are both. I conclude this is one of those as well.

The school is home for 103 homeless and abandoned street children, founded by a man whose story is inspiring and whose cause is certainly worthwhile. The children live in an old school compound and our tour operators regularly volunteer at the home. Our tour guide states that only education will make it possible to change their fate and we hear this view expressed a number of times. It explains how very seriously families take their responsibility to obtain good education for their children. Our group works with our guides for several hours, mostly cleaning and straightening up, while the children pretty much ignore all of us. Many of us help in the library where well-meaning donors have sent towering stacks of books for the use of the students. But there are far too many books for the available space and shelves and none of us can read Chinese to know which could be appealing to the children, who range in age from preschool to teenage.

What is clear is that the library doesn’t see much use. Neither does a music room, which has blankets carefully draped over the instruments to protect them from the silt and dust that is always present in both city and countryside. (All of the soil I see looks like a very fine silt that must drain quickly. Even with all the gardens we visit, I never see anything resembling a loam or compost—certainly nothing that looks as though it would till easily.) Instead, the children are pretty much wired to handheld electronic games and iPods. We don’t see their classes or any teachers about because it is a holiday but we hope they have enough teachers to really teach and mentor regularly enough to help the children want to read and learn. (In a separate conversation with a member of a volunteer American medical team, she expresses the same frustration with not knowing whether there are personnel to continue therapy with patients after the visiting foreign medical teams come in to perform operations and other medical interventions.)

Just like so much of China, no one is teaching the children not to litter. They eat and discard wrappings right and left just like Americans did until fairly recent times. The trash all about the countryside almost exactly resembles the trash Kenneth and I spent two years removing from the hillside behind our old Hot Springs, NC, cottage over the course of two years. There is so much of it that it is woven into the ground, grasses, vines and branches of shrubs and trees.

There are many parallels with the United States, except that China has so many more people to deal with and so the very rough times of our frontier and industrial development are compressed in time and magnified in scale many times over at the same time as expectations of achieving modern life in a single lifetime are very high. (China is nearly the size of the US but, at 1.4 billion, has over four times as many people. While we developed our abundant natural resources during the 19th and 20th centuries, China lost ground due to civil unrest, famine and war.) The Chinese people are proud to have accomplished the unity of their country in the mid-20th century and to have made huge strides in so few years. Individuals at every level of society hustle to get ahead while bold infrastructure investment tries to address persistent problems on every front. Still, much of the workmanship on buildings, at least at the level of finish, looks shoddy with large portions crumbled where they haven’t already been demolished. New construction is going on at a breakneck pace but, unlike Japan, much of it looks unsustainable for a long term.

The Chinese certainly have their work cut out for them and we can only admire their courage, hard work and determination. Our tour guide answers our questions with thoughtful, complex responses that attempt to describe the balancing act that the society and government is undertaking.